Predicate transformer semantics

Predicate transformer semantics was introduced by Dijkstra in his seminal paper "Guarded commands, nondeterminacy and formal derivation of programs". They define the semantics of an imperative programming paradigm by assigning to each statement in this language a corresponding predicate transformer: a total function between two predicates on the state space of the statement. In this sense, predicate transformer semantics are a kind of denotational semantics. Actually, in Guarded commands, Dijkstra uses only one kind of predicate transformers: the well-known weakest preconditions (see below).

Moreover, predicate transformer semantics are a reformulation of Floyd–Hoare logic. Whereas Hoare logic is presented as a deductive system, predicate transformer semantics (either by weakest-preconditions or by strongest-postconditions see below) are complete strategies to build valid deductions of Hoare logic. In other words, they provide an effective algorithm to reduce the problem of verifying a Hoare triple to the problem of proving a first-order formula. Technically, predicate transformer semantics perform a kind of symbolic execution of statements into predicates: execution runs backward in the case of weakest-preconditions, or runs forward in the case of strongest-postconditions.

Contents |

Weakest preconditions

Definition

Given S a statement, the weakest-precondition of S is a function mapping any postcondition R to a precondition. Actually, the result of this function, denoted  , is the "weakest" precondition on the initial state ensuring that execution of S terminates in a final state satisfying R.

, is the "weakest" precondition on the initial state ensuring that execution of S terminates in a final state satisfying R.

More formally, let us use variable x to denote abusively the tuple of variables involved in statement S. Then, a given Hoare triple  is provable in Hoare logic for total correctness if and only if the first-order predicate below holds:

is provable in Hoare logic for total correctness if and only if the first-order predicate below holds:

Formally, weakest-preconditions are defined recursively over the abstract syntax of statements. Actually, weakest-precondition semantics is a Continuation-passing style semantics of state transformers where the predicate in parameter is a continuation.

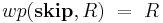

Skip

|

Abort

|

Assignment

We give below two equivalent weakest-preconditions for the assignment statement. In these formulas, ![R[x \leftarrow E]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/67e9c4023a9b7d4cd4144fee6128228d.png) is a copy of R where free occurrences of x are replaced by E. Hence, here, expression E is implicitly coerced into a valid term of the core logic: it is thus a pure expression, totally defined, terminating and without side effect.

is a copy of R where free occurrences of x are replaced by E. Hence, here, expression E is implicitly coerced into a valid term of the core logic: it is thus a pure expression, totally defined, terminating and without side effect.

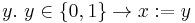

- version 1:

![wp(x�:= E, R)\ =\ \forall y, y = E \Rightarrow R[x \leftarrow y]\](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b6dbbe784d60d4139347bbaaf9e16b0e.png)

where y is a fresh variable (representing the final value of variable x) |

- version 2:

![wp(x�:= E, R)\ =\ R[x \leftarrow E]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/be4f9883888c061668a58ef9b1af6894.png) |

The first version avoids a potential duplication of E in R, whereas the second version is simpler when there is at most a single occurrence of x in R. The first version reveals also a deep duality between weakest-precondition and strongest-postcondition (see below).

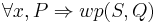

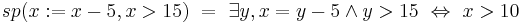

An example of a valid calculation of wp (using version 2) for assignments with integer valued variable x is:

This means that in order for the postcondition x > 10 to be true after the assignment, the precondition x > 15 must be true before the assignment. This is also the "weakest precondition", in that it is the "weakest" restriction on the value of x which makes x > 10 true after the assignment.

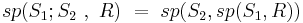

Sequence

|

For example,

Conditional

|

As example:

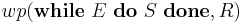

While loop

Weakest-precondition of while-loop is usually parametrized by a predicate I called loop invariant, and a well-founded relation on the space state denoted "<" and called loop variant. Hence, we have:

![wp(\textbf{while}\ E\ \textbf{do}\ S\ \textbf{done}, R)\ =\

\begin{array}[t]{l}

I\\

\wedge\ \forall y, ((E \wedge I) \Rightarrow wp(S,I \wedge x < y))[x \leftarrow y]\\

\wedge\ \forall y, ((\neg E \wedge I) \Rightarrow R)[x \leftarrow y]

\end{array}\](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/64b11e8c48f87cc2e83c75012e252547.png)

where y is a fresh tuple of variables |

Informally, in the above conjunction of three formulas:

- the first one means that invariant I must initially hold;

- the second one means that the body of the loop (e.g. statement S) must preserve the invariant and decrease the variant: here, variable y represents the initial state of the body execution;

- the last one means that R must be established at the end of the loop: here, variable y represents the final state of the loop.

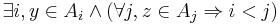

In predicate transformers semantics, invariant and variant are built by mimicking Kleene fixed-point theorem. Below, this construction is sketched in set theory. We assume that U is a set denoting the state space. First, we define a family of subsets of U denoted  by induction over Natural number k. Informally

by induction over Natural number k. Informally  represents the set of initial states that makes R satisfied after less than k iterations of the loop:

represents the set of initial states that makes R satisfied after less than k iterations of the loop:

Then, we define:

- invariant I as the predicate

.

. - variant

as the proposition

as the proposition

With these definitions,  reduces to formula

reduces to formula  .

.

However in practice, such an abstract construction can not be handled efficiently by theorem provers. Hence, loop invariants and variants are provided by human users, or are inferred by some abstract interpretation procedure.

Non-deterministic guarded commands

Actually, Dijkstra's Guarded Command Language (GCL) is an extension of the simple imperative language given until here with non-deterministic statements. Indeed, GCL aims to be a formal notation to define algorithms. Non-deterministic statements represent choices left to the actual implementation (in an effective programming language): properties proved on non-deterministic statements are ensured for all possible choices of implementation. In other words, weakest-preconditions of non-deterministic statements ensure

- that there exists a terminating execution (e.g. there exists an implementation),

- and, that the final state of all terminating execution satisfies the postcondition.

Notice that the definitions of weakest-precondition given above (in particular for while-loop) preserve this property.

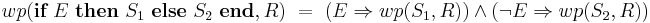

Selection

Selection is a generalization of if statement:

![wp(\mathbf{if}\ E_1 \rightarrow S_1 \ [\!] \ \ldots\ [\!]\ E_n \rightarrow S_n\ \mathbf{fi}, R)\ = \begin{array}[t]{l}

(E_1 \vee \ldots \vee E_n) \\

\wedge\ (E_1 \Rightarrow wp(S_1,R)) \\

\ldots\\

\wedge\ (E_n \Rightarrow wp(S_n,R)) \\

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/391261f62312cec5c88fa8a27baa16f3.png) |

Here, when two guards  and

and  are simultaneously true, then execution of this statement can run any of the associated statement

are simultaneously true, then execution of this statement can run any of the associated statement  or

or  .

.

Repetition

Repetition is a generalization of while statement in a similar way.

Specification statement (or weakest-precondition of procedure call)

Refinement calculus extends non-deterministic statements with the notion of specification statement. Informally, this statement represents a procedure call in black box, where the body of the procedure is not known. Typically, using a syntax close to B-Method, a specification statement is written

@

@

where

- x is the global variable modified by the statement,

- P is a predicate representing the precondition,

- y is a fresh logical variable, bound in Q, that represents the new value of x non-deterministically chosen by the statement,

- Q is a predicate representing a postcondition, or more exactly a guard: in Q, variable x represents the initial state and y denotes the final state.

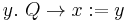

The weakest-precondition of specification statement is given by:

@ @![y.\ Q \rightarrow x:=y\ ,\ R)\ =\ P \wedge \forall z, Q[y \leftarrow z] \Rightarrow R[x \leftarrow z]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2841db73991017b8aa2f3b01b36df437.png)

where z is a fresh name |

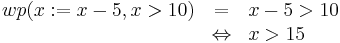

Moreover, a statement S implements such a specification statement if and only if the following predicate is a tautology:

![\forall x_0, (P \Rightarrow wp(S,Q[x \leftarrow x_0][y \leftarrow x]))[x \leftarrow x_0]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/212b7afbe88986ade5110e96d3cd3e58.png)

where |

Indeed, in such a case, the following property is ensured for all postcondition R (this is a direct consequence of wp monotonicity, see below):

@

@

Informally, this last property ensures that any proof about some statement involving a specification remains valid when replacing this specification by any of its implementation.

Other predicate transformers

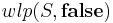

Weakest liberal precondition

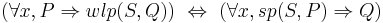

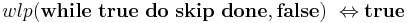

An important variant of the weakest precondition is the weakest liberal precondition  , which yields the weakest condition under which S either does not terminate or establishes R. It therefore differs from wp in not guaranteeing termination. Hence it corresponds to Hoare logic in partial correctness: for the statement language given above, wlp differs with wp only on while-loop, in not requiring a variant.

, which yields the weakest condition under which S either does not terminate or establishes R. It therefore differs from wp in not guaranteeing termination. Hence it corresponds to Hoare logic in partial correctness: for the statement language given above, wlp differs with wp only on while-loop, in not requiring a variant.

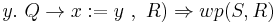

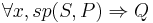

Strongest postcondition

Given S a statement and R a precondition (a predicate on the initial state), then  is their strongest-postcondition: it implies any postcondition satisfied by the final state of any execution of S, for any initial state statisfying R. In other words, a Hoare triple

is their strongest-postcondition: it implies any postcondition satisfied by the final state of any execution of S, for any initial state statisfying R. In other words, a Hoare triple  is provable in Hoare logic if and only if the predicate below hold:

is provable in Hoare logic if and only if the predicate below hold:

Usually, strongest-postconditions are used in partial correctness. Hence, we have the following relation between weakest-liberal-preconditions and strongest-postconditions:

For example, on assignment we have:

![sp(x�:= E, R)\ =\ \exists y, x=E[x \leftarrow y] \wedge R[x \leftarrow y]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/3e5832ff879064292d71d887048887bb.png)

where y is fresh |

Above, the logical variable y represents the initial value of variable x. Hence,

On sequence, it appears that sp runs forward (whereas wp runs backward):

|

Win and sin predicate transformers

Leslie Lamport has suggested win and sin as predicate transformers for concurrent programming.[1]

Predicate transformers properties

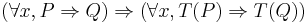

This section presents some characteristic properties of predicate transformers.[2] Below, T denotes a predicate transformer (a function between two predicates on the state space) and P a predicate. For instance, T(P) may denote wp(S,P) or sp(S,P). We keep x as the variable of the state space.

Monotonic

Predicate transformers of interest (wp, wlp, and sp) are monotonic. A predicate transformer T is monotonic if and only if:

This property is related to Consequence rule of Hoare logic.

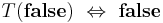

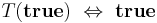

Strict

A predicate transformer T is strict iff:

For instance, wp is strict, whereas wlp is generally not. In particular, if statement S may not terminate then  is satisfiable. We have

is satisfiable. We have

Indeed, true is a valid invariant of that loop.

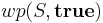

Terminating

A predicate transformer T is terminating iff:

Actually, this terminology makes sense only for strict predicate transformers: indeed,  is the weakest-precondition ensuring termination of S.

is the weakest-precondition ensuring termination of S.

It seems that naming this property non-aborting would be more appropriate: in total correctness, non-termination is abortion, whereas in partial correctness, it is not.

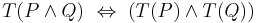

Conjunctive

A predicate transformer T is conjunctive iff:

This is the case for  , even if statement S is non-deterministic as a selection statement or a specification statement.

, even if statement S is non-deterministic as a selection statement or a specification statement.

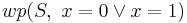

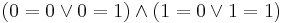

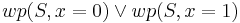

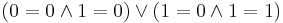

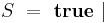

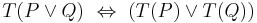

Disjunctive

A predicate transformer T is disjunctive iff:

This is generally not the case of  when S is non-deterministic. Indeed, let us consider a non-deterministic statement S choosing an arbitrary boolean. This statement is given here as the following selection statement:

when S is non-deterministic. Indeed, let us consider a non-deterministic statement S choosing an arbitrary boolean. This statement is given here as the following selection statement:

Then,  reduces to the formula

reduces to the formula ![R[x \leftarrow 0] \wedge R[x \leftarrow 1]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b6199b0d575524066abb1ad28d938178.png) .

.

Hence,  reduces to the tautology

reduces to the tautology

Whereas, the formula  reduces to the wrong proposition

reduces to the wrong proposition  .

.

The same counter-example can be reproduced using a specification statement (see above) instead:

@

@

Applications

- Computations of weakest-preconditions are largely used to statically check assertions in programs using a theorem-prover (like SMT-solvers or proof assistants): see Frama-C or ESC/Java2.

- Unlike many other semantic formalisms, predicate transformer semantics was not designed as an investigation into foundations of computation. Rather, it was intended to provide programmers with a methodology to develop their programs as "correct by construction" in a "calculation style". This "top-down" style was advocated by Dijkstra[3] and N. Wirth.[4] It has been formalized further by R.-J. Back and others in the Refinement Calculus. Some tools like B-Method provide now automated reasoning in order to promote this methodology.

- In the meta-theory of Hoare logic, weakest-preconditions appear as a key notion in the proof of relative completness.[5]

Beyond predicate transformers

Weakest-preconditions and strongest-postconditions of imperative expressions

In predicate transformers semantics, expressions are restricted to terms of the logic (see above). However, this restriction seems too strong for most existing programming languages, where expressions may have side effects (call to a function having a side effect), may not terminate or abort (like division by zero). There are many proposals to extend weakest-preconditions or strongest-postconditions for imperative expression languages and in particular for monads.

Among them, Hoare Type Theory combines Hoare logic for a Haskell-like language, Separation logic and Type Theory .[6] This system is currently implemented as a Coq library called Ynot.[7] In this language, evaluation of expressions corresponds to computations of strongest-postconditions.

Probabilistic Predicate Transformers

Probabilistic Predicate Transformers are an extension of predicate transformers for probabilistic programs. Indeed, such programs have many applications in cryptography (hiding of information using some randomized noise), Distributed systems (symmetry breaking). [8]

See also

- Axiomatic semantics — includes predicate transformer semantics

- Formal semantics of programming languages — an overview

- Hoare logic — the best-known axiomatic semantics

- Refinement calculus, an extension of guarded commands (and Hoare logic) exploiting the lattice structure of predicate transformers (for "refinement" order).

- Dynamic logic, where predicate transformers appear as modalities (in the sense of Modal logic).

Notes

- ^ Leslie Lamport, "win and sin: Predicate Transformers for Concurrency". ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 12(3), July 1990. [1]

- ^ Ralph-Johan Back and Joakim von Wright, Refinement Calculus: A Systematic Introduction, 1st edition, 1998. ISBN 0-387-98417-8.

- ^ Edsger W. Dijkstra, A constructive approach to program correctness, BIT Numerical Mathematics, 1968 - Springer

- ^ N. Wirth, Program development by stepwise refinement, Communications of the ACM, 1971 [2]

- ^ Tutorial on Hoare Logic: a Coq library, giving a simple but formal proof that Hoare logic is sound and complete with respect to an operational semantics.

- ^ Aleksandar Nanevski, Greg Morrisett, Lars Birkedal. Hoare Type Theory, Polymorphism and Separation, Journal of Functional Programming, 18(5/6), 2008 [3]

- ^ Ynot a Coq library implementing Hoare Type Theory.

- ^ Carroll Morgan, Annabelle McIver , Karen Seidel. Probabilistic Predicate Transformers, ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 1995 [4]

References

- J. W. de Bakker. Mathematical theory of program correctness. Prentice-Hall, 1980.

- Marcello M. Bonsangue and Joost N. Kok, The weakest precondition calculus: Recursion and duality, Formal Aspects of Computing, 6(6):788–800, November 1994. DOI 10.1007/BF01213603.

- Edsger W. Dijkstra, Guarded commands, nondeterminacy and formal derivation of program. Communications of the ACM, 18(8):453–457, August 1975. [5]

- Edsger W. Dijkstra. A Discipline of Programming. ISBN 0-613-92411-8. — A systematic introduction to a version of the guarded command language with many worked examples

- Edsger W. Dijkstra and Carel S. Scholten. Predicate Calculus and Program Semantics. Springer-Verlag 1990 ISBN 0-387-96957-8 — A more abstract, formal and definitive treatment

- David Gries. The Science of Programming. Springer-Verlag 1981 ISBN 0-387-96480-0

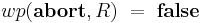

![\begin{array}[t]{rcl} wp(x:=x-5;x:=x*2\ ,\ x>20) & = & wp(x:=x-5,wp(x:=x*2, x > 20))\\

& = & wp(x:=x-5,x*2 > 20)\\

& = & (x-5)*2 > 20

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/207555b08f4c9dd2f502667b799c7107.png)

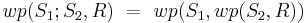

![\begin{array}[t]{rcl}

wp(\textbf{if}\ x < y\ \textbf{then}\ x:=y\ \textbf{else}\;\;\textbf{skip}\;\;\textbf{end},\ x \geq y)

& = & (x < y \Rightarrow wp(x:=y,x\geq y))\ \wedge\ (\neg (x<y) \Rightarrow wp(\textbf{skip}, x \geq y))\\

& = & (x < y \Rightarrow y\geq y) \ \wedge\ (\neg (x<y) \Rightarrow x \geq y)\\

& \Leftrightarrow & \textbf{true}

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/91584f0a60ec59a2abedac961b876852.png)

![\begin{array}{rcl}

A_0 & = & \emptyset \\

A_{k%2B1} & = & \left\{\ y \in U\ | \ ((E \Rightarrow wp(S, x \in A_k)) \wedge (\neg E \Rightarrow R))[x \leftarrow y]\ \right\} \\

\end{array}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a3522c51fac155e529edaaf568a975a6.png)

is a fresh name (denoting the initial state)

is a fresh name (denoting the initial state)

![S\ =\ \mathbf{if}\ \mathbf{true} \rightarrow x:=0\ [\!]\ \mathbf{true} \rightarrow x:=1\ \mathbf{fi}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d3f63db27af0de138dc2a7abd101d00c.png)